Air-Mechanization, Part 2: Airmobile Firepower

Part 1 outlined the development of the air-mechanized concept, which was born in the 1970s and was pursued in the 80s. At its inception, it held the promise of striking decisive blows in the enemy’s depth, giving it a critical role in the high-tempo mechanized warfare that was envisioned for the future. Yet the concept never really took off. Moving sufficient combat power which could survive enemy counterattacks proved challenging. Critics emphasized the fragility of the concept, which employed expensive yet flimsy means against objectives that were inevitably well-defended.

Since then, the two clearcut examples of operational-level air-mechanized assault have only supported this criticism. The 101st Airborne’s success in the Gulf War was predicated on overwhelming air superiority which made victory inevitable anyway, while Russia’s initial success in the highly-contested environment of Ukraine failed to accomplish anything decisive and was quickly beaten back. The second comes at an uncomfortable moment for mobile warfare in general, when long-range precision fires appear to have turned large-scale combat into World War I with missiles.

Yet long-range artillery, if employed in an air-mechanized role, might offer a solution to the very problem it introduces. If pushed to operational depths, its combination of range and firepower could allow it to strike enemy reserves and high-value targets while maintaining a relatively safe standoff. This would in fact follow the precedent of a technique explored in Vietnam.

Airmobile Firepower

The heliborne artillery raid was first employed by American forces tasked with defending large areas of South Vietnam. The Vietcong had complete freedom of movement outside the range of American firebases, so commanders experimented with airlifting entire batteries to remote locations where their presence was unexpected. Fire missions were then called in by patrols or air cavalry on enemy formations and headquarters. Raids could last from as little as twenty minutes to several days, during which the battery provided its own security.

These artillery raids played a strictly tactical role in a small war consisting of attritional search-and-destroy missions, not the fast-paced and dynamic offensives envisioned for air-mechanization. But they illustrate several essential points:

-Extending the reach of artillery into the enemy’s depths

-The use of terrain for protection

-Concentrating fires to destroy high-value targets

Assuming that ingress can be assured, long-range artillery—missile or tube—could be used operationally to disrupt the enemy’s rear area. Given enough time to work, it could destroy valuable targets and interfere with the movement of reserves, attracting disproportionate resources from the defender that would otherwise be committed to the main front.

The use of MLRSs in this capacity has been entertained for decades even in a strictly ground-based role. The development of the HIMARS raised the possibility of using it in an air assault role, although the system ended up being too close to the CH-53’s maximum sling-load capacity to lifted in a combat environment. Yet it is tantalizingly close, which raises the question of just what airmobile firepower would actually look like.

Ingress

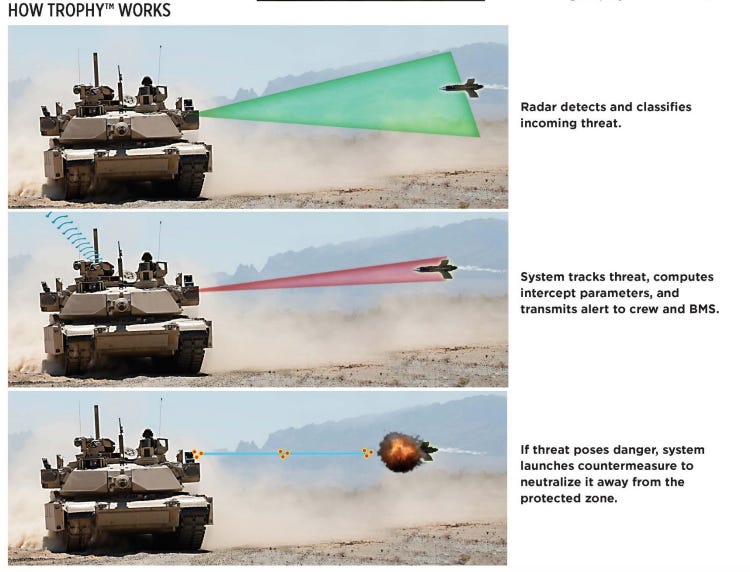

Before going any further, an obvious objection must be addressed: the proliferation of latest-generation MANPADS. Firing teams can be dispersed over a broad area and advanced MANPADS cannot be thrown off by flares. Although this can be mitigated somewhat by flying out-of-the-way routes, the threat remains persistent. The solution may lie in active protection systems decoupled from the platform itself. It is easy to imagine UAVs equipped with something like the Trophy, which intercepts short-range missiles and drones aimed at tanks, screening a rotary-wing formation on all sides during the ingress (this might also breathe new life into the role of the attack helicopter).

This does not remove the need to suppress the enemy’s radar-based air defenses, which might be done either as part of a general SEAD campaign or by creating a corridor through which low-flying helicopters can slip in (as the Russians did at Hostomel).

The General Outline

There are two broad schemes of maneuver for artillery-based air assault in the opening stages of a high-intensity war. The first is to deploy long-range fires at operational depth as a means of supporting ground forces’ advance. From there they can strike valuable targets (radars, air defenses, etc.), interdict the movement of reserves, and function in a counterbattery role. Standoff and mobility give these systems an inherent measure of protection, augmented by infantry and limited air defense; ultimately, however, their survivability would depend on the rapid breakthrough of ground forces.

The second approach is to establish a hardened position deeper in the enemy’s rear. Heliborne forces would secure the area and prepare for heavier reinforcements to be flown in fixed-wing aircraft—air defenses, EW equipment, and large quantities of supplies. The idea would be to hold out indefinitely under an umbrella of layered fires, impeding the enemy’s free movement on the ground and in the air, while building up enough strength to eventually launch ground attacks from it—effectively opening up another front. This is likely only possible in truly inaccessible areas such as mountain ranges.

Actions on the Objective

Let’s consider the first approach applied to the scenario laid out in an earlier piece, wherein a large mechanized army invades territory defended by a well-equipped forces. This was a fairly unimaginative extrapolation of existing patterns: long-range fires allow the defender to disrupt attacking columns long enough to reinforce forward positions, jamming up the advance and making it difficult for the invader even to deploy on a broad front.

Merely getting to the point where it could deploy requires an intense, closely-synchronized opening bombardment to suppress the enemy throughout its depth. Airmobile fires have a natural part to play in this. Inserted at depth, long-range artillery would have a faster targeting cycle than ballistic missiles, and unlike fixed-wing assets would be immune from air defenses once on the ground.

The tricky part, the details where the devil truly hides, is determining the proper mix of forces. The package must have enough firepower to swing the battle, but also be able to survive long enough that it actually does; at the same time, the commander understands that he faces very high odds of losing whatever he commits to this operation. Although the MANPADS threat biases the assault package toward the larger end—there is statistical safety in numbers—space for ammunition, fuel, supporting infantry, air defenses, etc. will unavoidably be at a premium. Ideally, it would be possible to resupply with subsequent waves, although this cannot always be counted upon. Striking the right balance is therefore highly sensitive to the specifics of the scenario.

No matter how favorable the terrain, an assault position will not be survivable beyond the opening days of the offensive. During that time, the greatest measure of protection comes from the intensity of the opening bombardment: air strikes, EW, ballistic missiles, special forces actions, cyber attacks, etc. This presents us with an apparent contradiction, however: the assault force depends on the same sort of fires that it itself delivers.

As noted above, artillery in depth has some advantages over air and ballistic missiles. But the contradiction is truly resolved when we consider the larger purpose of airmobile fires. It is not their destructive effects per se, but the dilemma posed by their presence in depth during the ground advance that truly disrupts the defense. Success is measured by the disproportionate resources required to neutralize them, competing with all the defender’s other priorities; they are one piece of the synergy accomplished by simultaneous effects. A rough priority of fires might therefore be:

-High-value targets that pose immediate threats to the assault force (radars, EW equipment, artillery, etc.)

-High-value targets that have a large and immediate impact on the main battle (command posts, comms)

-Operational reserves moving forward

-Tactical defenses engaged with ground forces

-Targets that degrade the defender’s overall position (supply depots, transportation links)

Any other threats to the assault force must be prioritized on an ad-hoc basis, preferably engaged by rotary-wing or other ground forces.

2022 Redux

To put some flesh on these bones, let’s imagine a redo of Russia’s 2022 invasion on the Kiev front where both sides are much better prepared and equipped. This is a useful scenario because Russia’s actual failure here looked very similar to what a headlong charge against a modern defense might look like, albeit for different reasons. Its columns got stuck as it was unable to deploy over a wide area or secure its lines of communication—much the same as would happen with carefully selected long-range targeting.

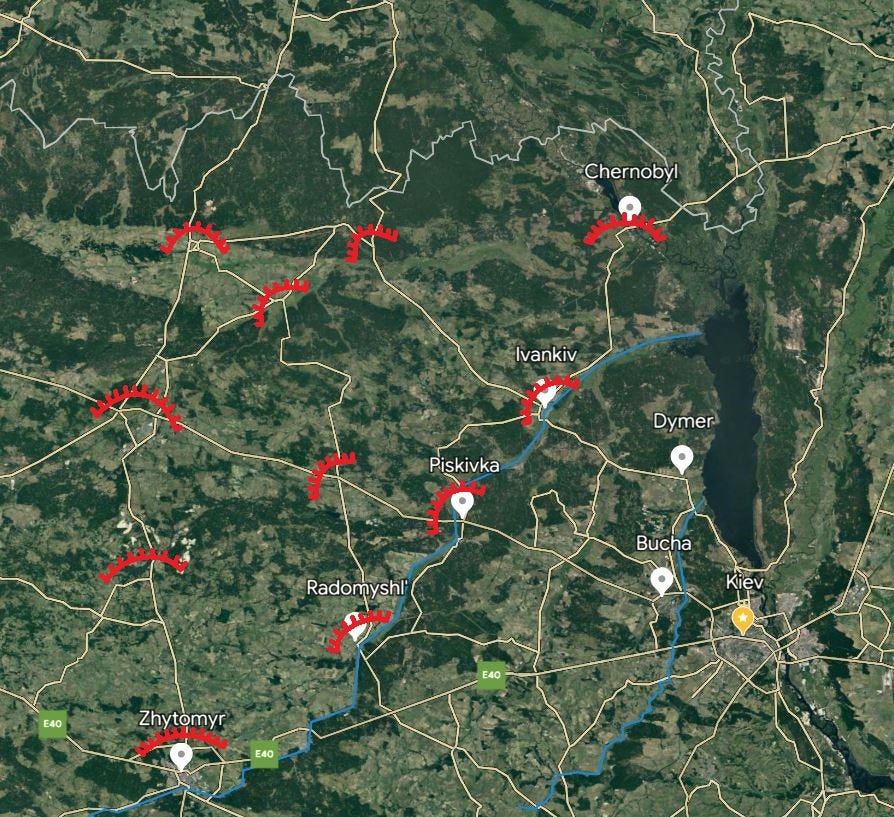

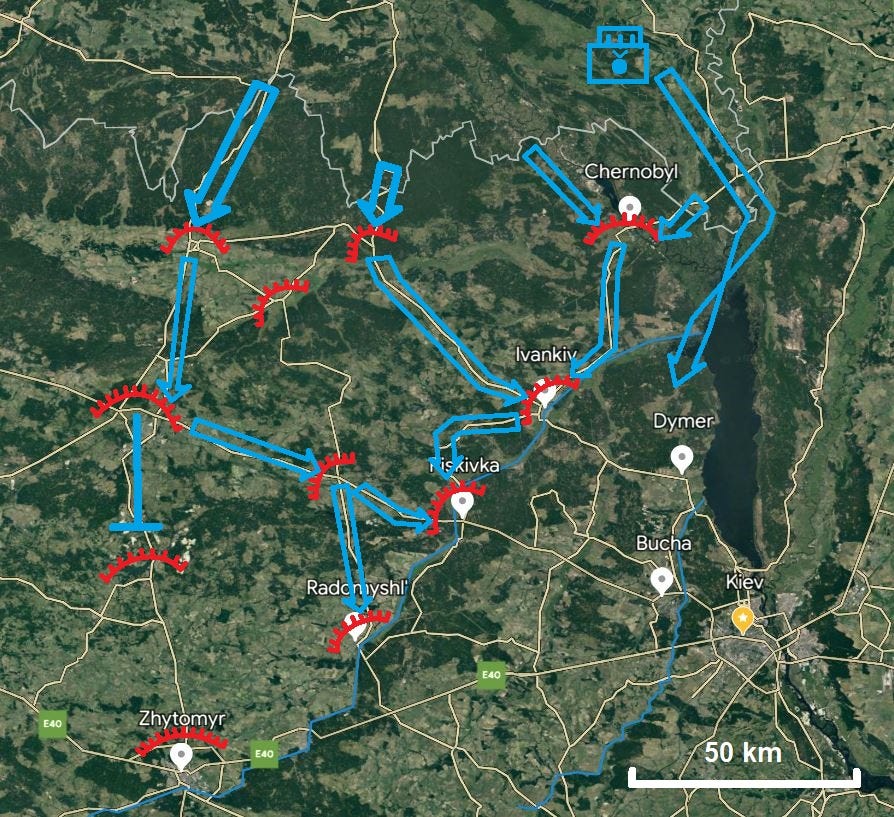

Anticipating much stiffer resistance this time, Russia has gone through rigorous rehearsals and organized its march columns to push through the forward defenses. First-day objectives are the bridgeheads over the Teteriv River across a 70-km front, with blocking forces in the direction of Zhytomyr, to allow for a subsequent push on the capital. Ukraine has meanwhile positioned mechanized reserves along the Irpin and has prepared forward defensive positions west of the Teteriv. Here’s the kicker: in this scenario, Russia also has HIMARS (the reader will forgive the contrivance for the sake of demonstration).

Soon after H-hour, a platoon of 4 HIMARS and reloaders are sling-loaded on Mi-26s to the woodlands just south of the Teteriv’s confluence with the Dnieper. They are accompanied by a battery of tube artillery, an air defense battery, and an infantry battalion, which establishes patrols and blocking positions. Mi-24s and Ka-52s remain in overwatch, protected by a screen of APS-equipped drones. A pair of interceptors patrols further back and EW systems continuously jam Ukrainian radars.

The area is cut through by a square grid of dirt roads, allowing HIMARS to move between firing positions under the partial concealment of a dense evergreen canopy. From there they can range the ground element’s entire deployment zone, from Ivankiv south to Radomyshl’, and all the roads back to Kiev. Even with substantial supporting assets, the assault force faces long odds against the reserves positioned between Bucha and Dymer (although these odds drastically improve as the ground element approaches supporting range around Orane).

In such circumstances, those reserves might become the highest priority, with reconnaissance assets drawing up target lists during the ingress. Regardless, within the space of just a few hours the assault force can target valuable military infrastructure as far as the opposite side of Kiev, impede the movement of reserves, and force the commitment of valuable resources that are needed elsewhere.

Fast and Slow

This scenario is a mixture of actual events, plausible adaptations, and non-existent weapons. Although that can prove nothing, it does show how airmobile fires could fulfill the original promise of air-mechanization.

Airmobile fires are moreover versatile. Successful employment in the manner described above hinges on tempo and synchronization, creating a small window that greatly magnifies efforts elsewhere. The third and final part in this series will look at a much slower-paced concept for artillery in air assault: creating firebases within the enemy’s depths. It will also conclude by looking at the prospects for air-mechanization across the world in the next few decades.

Thank you for reading the Bazaar of War. Most articles are free for all to read, but a subscription option is available to all who wish to support. Subscribers receive a pdf of the critical edition of the classic The Art of War in Italy: 1494-1529, and will have exclusive access to occasional pieces.

You can also support by purchasing Saladin the Strategist in paperback or Kindle format.

"This is likely only possible in truly inaccessible areas such as mountain ranges." Shouldn't we start thinking of urban areas like mountain ranges as it concerns accessibility?