Force Structure for the Future: Bring Back the Regiment?

Modern ground forces are torn between two competing demands, for infantry and for enablers. Urban operations and large-scale combat over the past decade demonstrate that infantry remains just as essential as ever. Yet that same infantry needs a lot of low-level support just to survive and remain effective: drone operators, EW, and engineers, not to mention armor and artillery. This poses an obvious dilemma for force management—not least when faced with competing demands for air, naval, and missile assets—but also raises questions about force structure.

Organizing the Force

One of the key decisions in how future wars will be fought is what will be the primary tactical unit. Inevitably, certain command levels are much more important than others: those which require greater freedom from higher headquarters than they allow their own subordinates. This partly comes down to a question of where the combined-arms fight is best coordinated, which in turn depends heavily on technology.

This has varied a lot over time. The main tactical formation of the Napoleonic army was the corps, which had organic artillery, cavalry, and engineers that allowed it to fight independent actions with a versatility not available to smaller units. The Western Front of World War II was a war of divisions at the tactical level and armies at the operational, a pattern which continued through the Cold War. The US Army shifted to a brigade model during the GWOT era, on the assumption that future deployments would be smaller scale and lower intensity; only recently has it made the decision to return to a divisional model. Russia also switched to a brigade model around this time, although more for cost and manpower reasons.

Tweaking the Hierarchy

At the same time, certain echelons have disappeared altogether. The subdivisions of Western armies reached their greatest extent in World War I, as new ones were added at the extremities of the model standardized during the French Revolution: fireteams/squads to execute trench raids, army groups to manage large sections of the front. At the same time, cuts were made around the middle. Machine guns were pushed from the regimental level down to battalions over the course of the war, reducing the number of these bulkier regiments in a division; this accordingly eliminated the need for brigades as a tactical unit.

This continued with the next major war. More organic supporting arms and increased mobility made combat more dispersed, creating the need for supply, communications, intelligence, and medical support at lower levels. As units at each echelon grew fatter, it became too cumbersome to have six separate headquarters from battalion to field army. Midway through World War II, the Soviets followed the Western example of eliminating brigades, and got rid of corps to boot (excepting ad-hoc and specialized formations). During the Cold War, the increasing use of combined arms at a lower level caused most NATO militaries to eliminate the regiment/brigade distinction altogether: the majority favored the larger brigade, which could receive supporting units to fight as a brigade combat team, although the US Marines retained regiments as brigades in all but name (the French, by contrast, got rid of most of their battalions, preferring regiments formed of many companies).

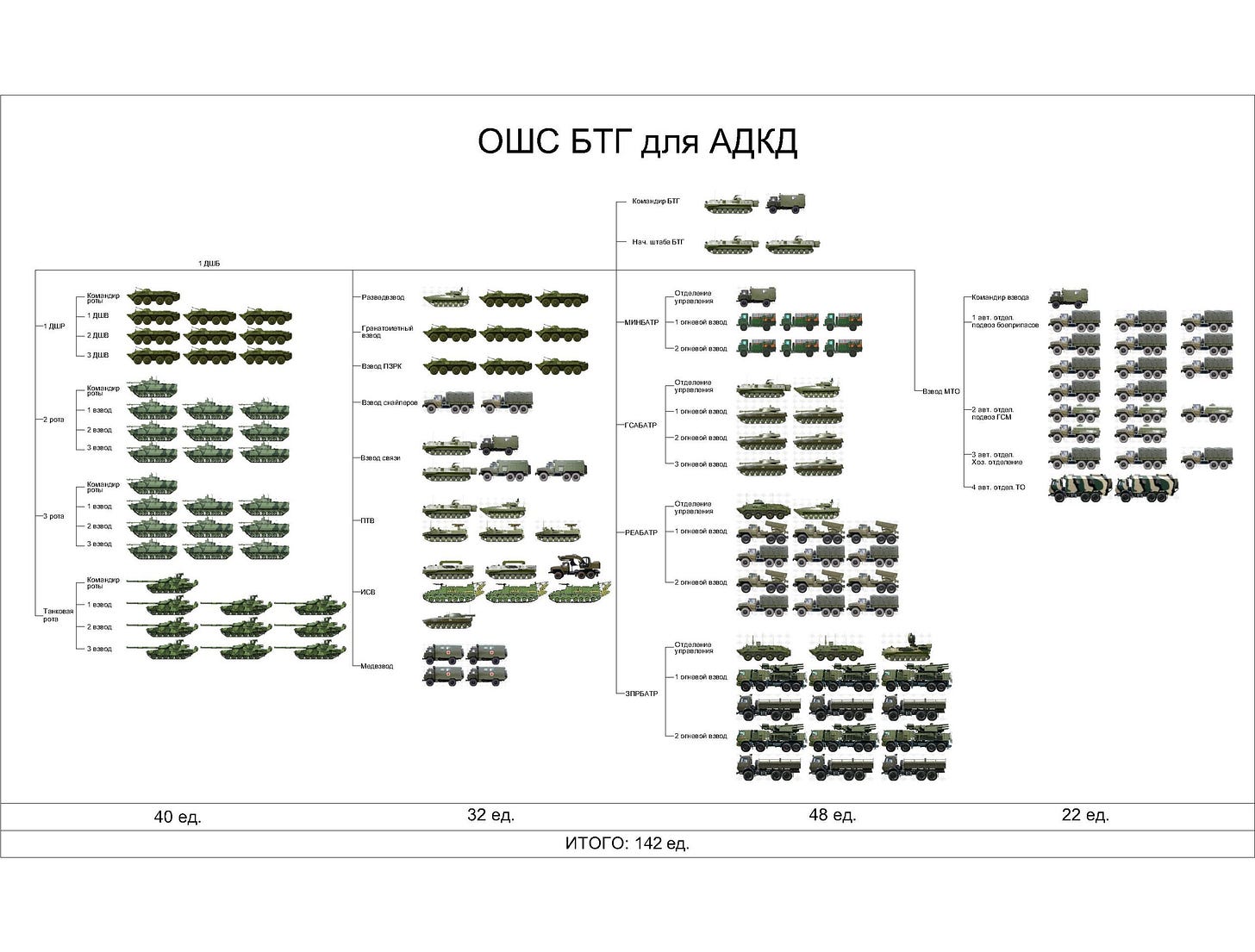

The Battalion Tactical Group

Alongside the long-term trend pushing combined arms down to lower levels, there is the question of additional support: the engineers, EW, communications, air defense, etc. (the use of drones at all echelons exemplifies the increasing requirements for both combat and non-combat support). The ever-greater strain that these parallel trends impose on low-level staffs makes an eventual force restructuring inevitable.

The Russians have gone the farthest in experimenting with this problem with the Battalion Tactical Group (BTG). This was a semi-permanent task force organized around an infantry battalion which incorporated a tank company, artillery batteries, EW, UAVs, and other assets. It should be emphasized however that this was not intended to be a complete devolution of combined arms to the battalion level, but rather a means to straddle broad-ranging requirements. Only one battalion in a brigade was to function as a BTG at a time, manned mostly by professional contract soldiers on 6-month readiness cycles. The idea was that BTGs stood ready to mobilize for small-scale contingencies, such as the 2008 Georgia War, while a larger conflict would require a mobilization period to fill out the other battalions; in the event of large-scale war, combined arms would be conducted at the brigade, not battalion, level.

The task of controlling four company-sized maneuver elements while coordinating fires and directing all other attachments places a heavy burden on an ordinary battalion headquarters. But it is difficult to judge the effectiveness of BTGs in combat: they appeared to deploy with their parent brigades during the invasion of Ukraine, and it is unclear the extent to which they fought as BTGs. The Russians had visible difficulties coordinating arms at a low level, although these were not necessarily the professional soldiers.

The Marine Littoral Regiment

The US Marine Corps has meanwhile faced the problem of how to employ its battalions in a potential conflict with China. The Marine Littoral Regiment was designed to operate on remote islands of the western Pacific, where they could easily be cut off and destroyed in detail. This consists of an infantry battalion with an organic anti-ship battery, an anti-air battalion, and a logistics battalion equipped to provide amphibious logistics support.

Tellingly, this follows the same structure of all Marine task forces: a ground element, an aviation element, and a logistics element. It is essentially expeditionary, focused on a narrow mission set. But if the BTG places too much of a burden on a single battalion staff, the MLR underloads the regimental staff for everything outside of that mission set. There is as yet no standing formation that pushes the combined-arms battle down to a lower level in a manageable way.

Splitting the Difference

One possible solution is to reintroduce the brigade/regiment distinction. Brigades could remain standing combined-arms formations, with their own artillery, armor, etc., while subordinate regiments prosecute the combined-arms fight at the lowest level. Regimental staff could manage enablers—synchronizing EW coverage, constructing fortifications, integrating the UAV picture—and provide fire direction for infantry battalions dispersed over a wide area, without task-saturating the battalion command. Crucially, this would not require the expansion of the brigade beyond additional staff, allowing it to fit within a divisional organization (although it would allow for increasing the proportion of enablers without straining the command structure).

There are a number of ways this might be done. Brigade could retain the option of exercising direct control over its artillery and maintain responsibility for coordinating higher-level fires—regiments could even be “floating” staffs that are only assigned subordinate units on a provisional basis. Or, higher-level fire coordination could become a division responsibility, in which case the brigade would revert to more of an administrative and training role in most cases. Likewise, battalion headquarters could be deprecated to an administrative/training role, with the regiment exercising direct control over its companies.

There is one other way in which an additional layer of staff might be necessary. Increasing numbers of UAVs at all levels down to the squad represents not just an expansion of organic assets, but of command-and-control capacity. Saturated drone coverage affords higher headquarters an unprecedented ability to direct battle; this, combined with AI and better systems integration, will cause staff sizes to balloon beyond what makes sense for a single battalion.

Bringing back the brigade/regiment distinction is just one way of tackling what is bound to be a difficult problem. We will undoubtedly see militaries try a variety of different organizations, some of which are likely to be far more radical. We cannot even foresee what new factors or technologies will shape requirements, making it hard to imagine a stable equilibrium emerging in the foreseeable future. The only overriding certainty is that organizational structures will have to remain ever flexible.

Thank you for reading the Bazaar of War. Most articles are free for all to read, but a subscription option is available to all who wish to support. Subscribers receive a pdf of the critical edition of the classic The Art of War in Italy: 1494-1529, and will have exclusive access to longer monthly pieces.

You can also support by purchasing Saladin the Strategist in paperback or Kindle format.

The only opportunity from reorganization is for highly motivated change agent leaders to take advantage of the chaos and confusion of reorganization to push through a reform agenda at their level. The last time this was done was in 2006-2007 by Petraeus and Company, you may call it The Surge, or Counter-Insurgency , and yes at cost.

The time before that was Perry and the last supper where the defense industrial base was gutted in 1993.

I was serving during both periods.

Neither was an unmitigated good, putting it mildly. The point is great changes can happen, if the opportunity is taken.

"There is one other way in which an additional layer of staff might be necessary. Increasing numbers of UAVs at all levels down to the squad represents not just an expansion of organic assets, but of command-and-control capacity."

There is a corollary to this increased capability: modern battlefields are going to be absolutely saturated with cheap sensors; Quadcopter-ferried seismometers, balloons and gliders with ELINT modules, your imagination is the limit.

In that environment, good small-team training (2-6 men) will be vital, with their radios treated like a high-risk weapon. The best Order of Battle will be one that minimizes their signature while still putting support elements where they need to be.

Are modern militaries even able to accept the autonomy and speed this will require?