Entangled Conflicts: Hydras and Siamese Wars

It is something of a miracle that a major war did not engulf Europe in the 1770s. The continent had already been wracked by several large-scale conflicts that century—the Wars of the Spanish and Austrian Succession, the Great Northern War, the Seven Years’ War—and was yet again poised on the brink. The French, Spanish, and Dutch were providing covert support to the colonial revolt in North America, while tensions mounted in the German states over the succession to the Electorate of Bavaria; Russia eyed these developments from the sidelines, eager to jump in at an opportune moment.

Yet when hostilities did break out in 1778—France declared war on Britain, Prussian forces crossed into Habsburg territory—this failed to activate the old alliance systems and spark a general war. The War of the Bavarian Succession, as the Austro-Prussian war came to be known, was limited to maneuvers in Bohemia, and was settled diplomatically the following year. Hostilities between Britain and France, joined by Spain in 1779 and the Dutch in 1780, was mostly limited to North America and the high seas. Why did these various tensions not spark a wider conflagration?

Ghosts of the Diplomatic Revolution

Ultimately, it came down to the decision of France. Two decades earlier, she and Austria had put aside their ancient animosity to sign a defensive treaty, implicitly against Prussia and Britain. The alliance was unpopular in both countries and ultimately profited neither. France was already moving away from a policy of expansion on the Continent, focusing instead on its colonial rivalry with Great Britain; supporting Austria was ruinously expensive, and only distracted from more important theaters. Austria, for its part, profited from generous financial and military support at first, but saw this largely reduced after reverses early in the war.

In a sense, then, the allies fought two entirely separate wars. France defended her colonies in the Americas and India while overrunning King George II’s continental possession of Hanover; Austria was entirely absorbed by the war against Prussia. So too on the other side of things. Britain fought France at sea and on land, aided by only minor Prussian interventions, while Frederick the Great desperately fought off the Austrians and Russians.

Yet it would be wrong to say that the two were unrelated. They were more like Siamese twins: actions in each theater affected the calculations of all belligerents, and it was very hard to disentangle various parties’ separate interests. Neither Britain nor France wanted to abandon their respective alliances for fear that it would leave them vulnerable to a much stronger coalition, with the perverse effect of prolonging both conflicts; the war was only concluded with a general peace at the consent of all parties.

The War That Wasn’t

Viewed through this lens, France’s decision not to honor her treaty with Austria in 1778 was eminently reasonable. French finances were in no shape to endure a protracted war, which would moreover undermine her limited strategic objectives vis-à-vis Britain. As a result, the Anglo-French conflict remained a lower-intensity war that lasted only five years—much shorter than previous coalitionary wars in Europe, even with the eventual participation of the Spanish and Dutch. The War of the Bavarian Succession was less than a year, and saw no real fighting.

It was not only the simplification of strategic calculations that allowed things to be resolved relatively quickly. Contemporaries were sharply aware of the possibility of a general European war and desperately hoped to avert it. Frederick in particular knew that the longer fighting lasted, the greater the odds of a French intervention, deciding not to press his advantages and remaining open to a settlement. It is hard to imagine, by contrast, the war being settled so quickly if the British and French once again began subsidizing the eastern war. Smaller German rivals would have inevitably gotten sucked in, Hanover would have once more been at stake, and diplomatic negotiations would have been greatly complicated.

Siamese Wars

1756 and 1778 present contrasting examples of what parallel wars can look like on a complicated political map. The European alliance system which had evolved over several centuries meant that they usually wind up more like the former than the latter. The War of the Austrian Succession, which ended just eight years before the Seven Years’ War broke out, was also several conflicts at once (and was indeed seen as such by contemporaries):

The First and Second Silesian Wars that Frederick the Great launched on Saxony and Austria

France and Spain against a coalition of their neighbors

Colonial wars in Asia and the Americas between France and Britain

In the same vein, one could go so far as to describe the Anglo-French colonial rivalry as a concatenation of separate conflicts. Each theater was its own war, fought for separate stakes: Quebec, the Caribbean, India, Senegal, etc. These were united by the war at sea, which determined their ability to maintain supply, but victory or defeat in one theater hardly affected prospects elsewhere. It is telling that colonial militias in North American began fighting in 1754, two years before the Seven Years’ War broke out.

The fighting in India, the Carnatic Wars are an even better example of this. Although sparked by Anglo-French competition, they also drew in Indian princes motivated by purely local concerns, and European troops constituted a minority of combatants. The Second Carnatic War was fought in the early 1750s during a time of peace in Europe.

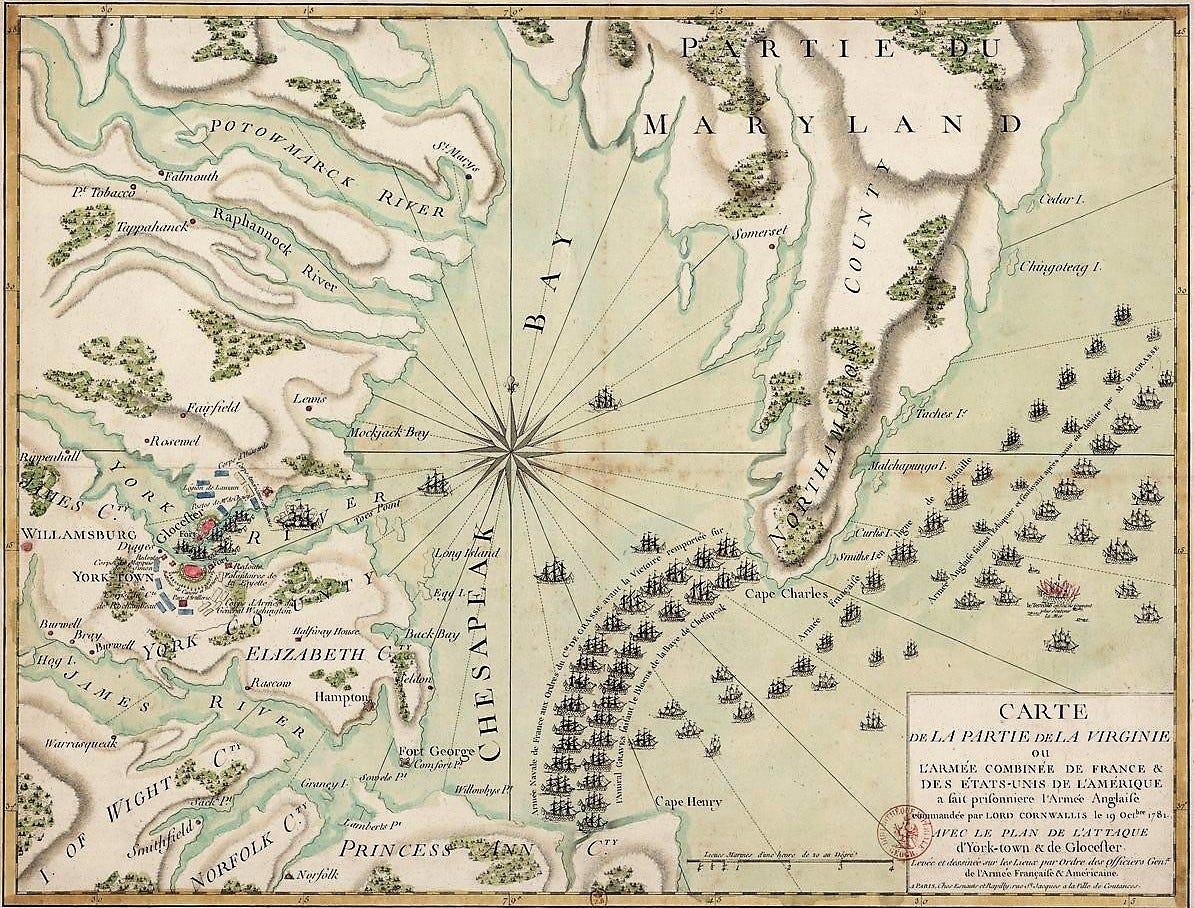

In a more limited sense, the wider War of American Independence was also a Siamese conflict. It was born of France’s older naval rivalry with Britain, and rapidly expanded beyond North America to the Caribbean, Atlantic, and Indian Ocean. It even saw fighting in continental Europe: although diplomats avoided getting embroiled in the concurrent Austro-Prussian war, Spanish and French forces besieged Gibraltar for nearly four years. The larger war was only ended by comprehensive negotiations at Paris among all parties involved.

World War II

It was not just the peculiarities of the ancien régime alliance system that created these sorts of conjoined conflicts: the Second World War was a clear such example on a global scale. The war in Asia began in 1937, while that in Europe did not begin until 1939. Germany and Japan were allied the whole time but did not coordinate strategy in any meaningful way, while other European powers’ colonial interests in Asia were decidedly peripheral to the war against Germany. It was not until the United States entered the war in 1941 that it became a unitary struggle.

Yet however much the fighting in both theaters was presented as part of a single war, policy debates made clear how much their respective aims stood in conflict. America’s stated Germany-first policy conflicted with the pressing need to arrest and roll back Japan’s gains. The equipment needed for a large ground campaign and convoy escorts across the Atlantic competed for manufacturing capacity with the carriers, refuelers, and planes needed for island hopping in the Pacific. America’s efforts toward one strategic objective inevitably came at the expense of the other.

Unitary Alliances

Unlike these tradeoffs that affected a single power, coalitions organized around the defeat of a common enemy faced very different dynamics. Campaigns in every theater could be designed either to contribute directly to that end, or to complement efforts in another theater. The Nine Years’ War and War of the Spanish Succession both saw massive coalitions formed to curb Louis XIV’s ambitions, coalitions which operated with remarkable harmony. This eventually broke down at the end of the latter war, when British and Dutch security concerns were met, but up to that point, their actions in all theaters were coordinated toward this end.1

The Napoleonic Wars were a reprise of the same. Various powers often pursued individual interests (especially before 1812), but were for the most part concerted in their common goal of defeating France. Likewise, all major powers in World War I realized that they could only accomplish their individual objectives with the defeat of the opposing coalition (in all such cases, the length and intensity of the conflict is determined by the combined resource bases of each bloc, not diplomatic complications that prolong an otherwise short war). So too in the Second World War: even as American efforts in Europe detracted from the Pacific, they complemented Soviet efforts on the Eastern Front.

The Modern Hydra

The post-1945 era has looked very different from any previous time. Nuclear weapons have made the great powers reluctant to enter into direct conflict with one other, but this has not resolved the underlying sources of tension: instead it has diverted that energy into proxy wars. These sorts of conflicts are even more intractable than Siamese wars, because it is very difficult to solve the underlying tensions that drive them. Sometimes this can be done on a provisional basis—the 1953 armistice that ended the Korean War saw China and America pressure their allies to end the First Indochina War. But sponsors may always reactivate their proxies when it is diplomatically useful, and even when a conflict can be decisively ended, the wider competition can be resumed in another theater—proxy wars are a many-headed hydra.

The post-1990 world is more complicated still, not so neatly divided between two blocs. European countries supported both sides of the Libyan civil war, while rival factions in Syria were backed by different US agencies. As both these examples suggest, there is more room and incentive for external powers to provide patronage, with a concomitantly greater risk of these spilling over into messy regional conflagrations. These combine Siamese conflicts with external proxy relationships, creating hopelessly tangled general states of war.

The UAE’s relationship with Sudan’s Rapid Support Force (RSF) illustrates this. The RSF furnished fighters for the Emiratis in Yemen, which has been reciprocated with material and financial support in the ongoing Sudanese civil war. In doing so, the UAE is undermining Egypt’s interests in Sudan, despite their recent cooperation backing General Haftar in Libya. This comes at a time of increasing pressure for regional actors to reengage the Houthi threat in Yemen.

This comes at a time of expanding scope for outside powers to intervene in localized disputes. Modern warfare has seen a multitude of technological niches that need to be filled, from UAVs to missile systems to cyber capabilities; those systems also require personnel with the necessary technical expertise, while worldwide demographics drive demand for raw manpower; finally, money remains paramount as always. Although we may reasonably hope that direct superpower conflict will remain a distant threat, that will not diminish the prospect of violence in the coming decades.

Thank you for reading the Bazaar of War. Most articles are free for all to read, but paid subscriptions are available to all who would like to support. Subscribers receive the critical edition of the classic The Art of War in Italy: 1494-1529 and will have exclusive access to occasional pieces.

You can also support by purchasing Saladin the Strategist in paperback or Kindle format.

As an interesting aside, however, this ran a slight chance of expanding into an even larger free-for-all. Concurrent with the fighting in Western Europe was the Great Northern War, a titanic struggle around the Baltic between the Swedish Empire and a coalition of Russians, Poles, Saxons, and Danes. Louis tried to get the Swedish king Charles XII to attack the Holy Roman Empire, which would have conjoined both conflicts, but the Allies were successful in dissuading him.

I have a Grand Theory about Britain in the 1700s and 1800s: they had a lot of colonial mass outside the tropics, while the other great power were almost entirely in the tropics. Slavery can be very profitable in the tropics, but not so much outside it, for various logistical reasons around keeping slaves from escaping. By banning slavery, and enforcing it with their navy, the Brits applied a lot of pain to their competitors, and to the new USA, without undergoing much pain themselves.