Theaters of Operation and the Potential for War

The expressions “theater of operations” and “theater of war” have often been used interchangeably. This is mostly a relic of history. Although the latter term is much older, it was associated from the outset with what we today call the operational level of war: a theater of war referred to the geographical area where a single army could independently operate. By the time of the World Wars, the label “operational level” had not yet entered the English language, leaving us with terms such as the “European Theater of Operations” and “Pacific Theater of Operations” to denote areas encompassing several thousands of miles.

In the later 20th century, however, a clear distinction emerged: a theater of war was where strategy played out, while a theater of operations was limited to the operational. In general terms, this means that the one is defined more by political boundaries, while the other is most often defined by physical geography.

Simple enough. But if one looks beyond the bounds of individual wars to historical patterns of conflict, this relationship between the political and geographic becomes more complicated. Whatever territorial concerns animate a particular war, fighting tends to spread to wherever the two sides can hit each other. Certain theaters of operations may constitute primary objectives in their own right, useful avenues toward some larger objective, or mere secondary theater to bleed out the other side. Nearly any boundary that two belligerents or their allies share is a potential theater of operations, as shown in the great coalitional wars of the 17th and 18th centuries.

Operational Considerations as Drivers of War

At the same time, political objectives are not completely arbitrary. Wars to acquire territory are usually fought with an eye to some military or economic advantage. Although borders tend to settle eventually on some defensible natural obstacle, such as a river or mountain range, sometimes there is no neat territorial division: the military advantage conferred by a certain piece of the frontier is so great that it poses an existential threat to the other side.

The Golan Heights are a quintessential example. The high ground on the east bank of the Jordan forms a corridor between the interior and the coast, flanked by the Syrian coastal ranges on the north, and the Sea of Galilee and desolate rough terrain to the side.

Whichever side possesses the Heights can descend to the fertile valley below, which forms the agricultural heart of any coastal state, or march unimpeded in the other direction to Damascus or the rich farming region of the Hauran.

This makes their possession by one side intolerable to the other, making it a constant point of contention since Biblical times: between the Kingdoms of Israel and of Aram (centered on Damascus) in the 9th century BC, the Crusaders of Jerusalem and the emirs of Damascus in the 12th century AD, and between modern Israel and Syria in the 20th. Although tactics have drastically changed over the ages, geography continues to make this a natural theater of operations.

When possession of one piece of ground is an existential threat to both neighbors, however, neither tends to be long-lasting. Jerusalem and Damascus have fallen under the same ruler more often than not over the past 3,000 years.

The Operational Defining the Theater of War

More interesting cases arise when a borderland 1.) gives an extraordinary advantage to whichever side possesses it, 2.) is valuable in its own right, and 3.) it is defensible in part. This is true of major river valleys, which can serve as an avenue of advance just as much as a barrier (to say nothing of their economic value).

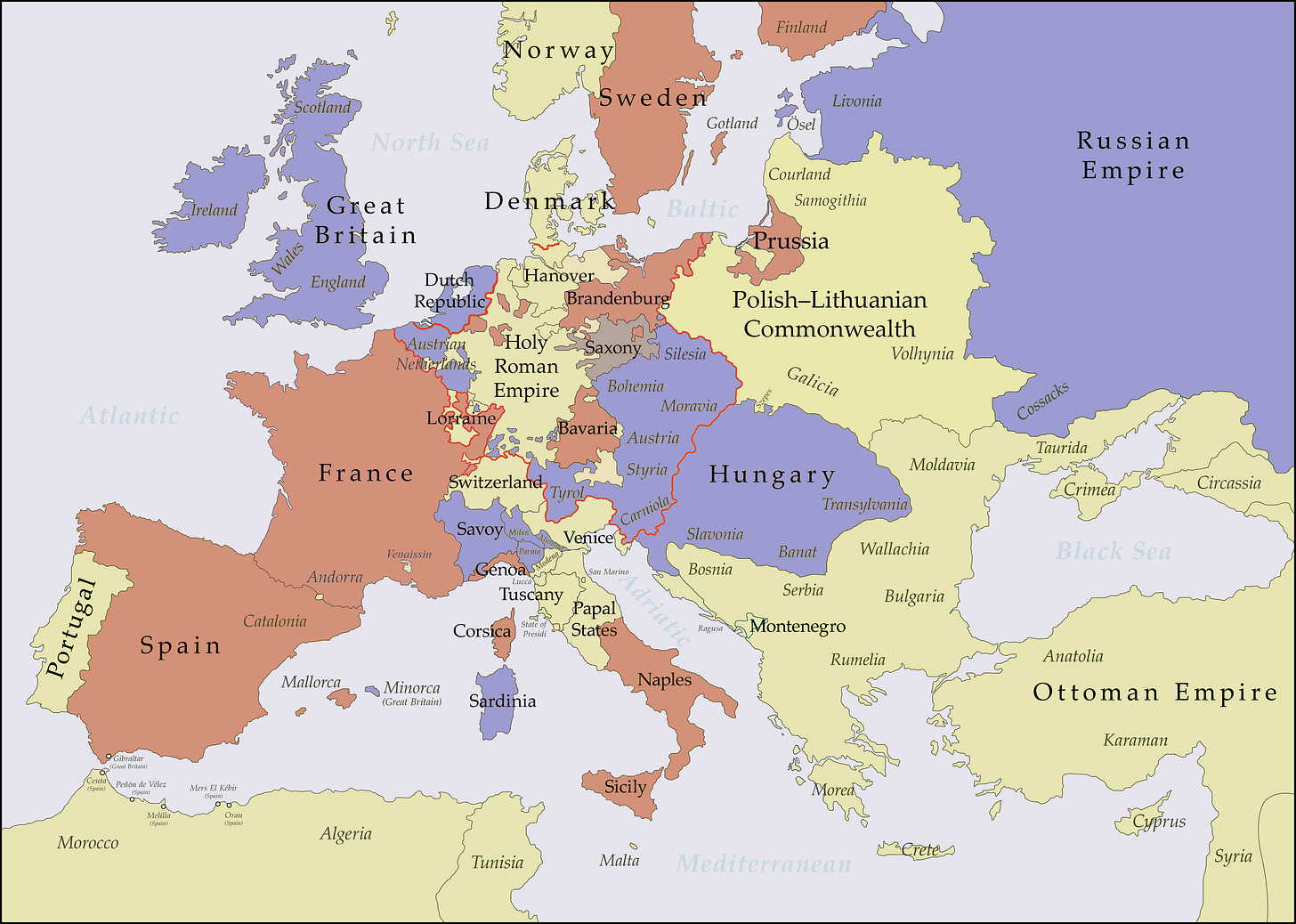

These reasons made the Low Countries, which stretch from northern France to southern Holland, a perennial theater of operations in European wars—the “cockpit of Europe”. The same geographic features that made the region capable of supporting large armies (fertile soil and plenty of rivers that were conducive to logistics) also made it difficult to conquer outright, furnishing plenty of obstacles that could be used as defensive lines.

Yet bordering states could not afford to be passive: even if defensible, it required plenty of effort and expense to man and fortify these areas. France suffered at least one major invasion from this direction every century from the 13th to the 20th, made more dangerous by the short distance to Paris. The Dutch Republic likewise fought off Spanish armies along the southern border during its long war of independence in the 16th and 17th centuries, and was nearly overrun by the French in 1672.

Larger strategic questions also drew in countries farther afield. England feared that any major power should be able to use Antwerp as a port. The princes of the Holy Roman Empire realized that a France secure on her northern flank would be free to direct all her energies to the Rhine. Likewise, Spain her holdings in the Netherlands as a way to contain France. It was therefore almost impossible for war to break out in the Low Countries without it drawing in many other powers. A natural theater of operations—an enduring product of geography and human economy—therefore gave shape to an entire theater of war.

By contrast, the example of China shows how the purely military aspects of geography are not enough. Although the Yellow and Yangtze Rivers occasionally formed frontier zones during periods of fragmentation and wars of dynastic succession, this always proved short-lived. Whatever defensive advantage they gave was far outweighed by the economic and manpower advantages of controlling the surrounding plains; the rivers were more a driver of unification than of division.

Theaters of War

Geography is much longer-lasting than political configurations, but these can be durable too, in some cases creating “natural” theaters of war. The Italian Wars turned all of Western Europe into a perpetual theater of war. The interests of several large and well-established monarchies—Spain, France, the Holy Roman Empire—got so entangled during the Italian Wars of the early 16th century that it became virtually impossible for war to break out between two states without things spiraling into a much larger conflict. Italy, like the Low Countries, was desirable territory in itself and situated between Habsburg and French lands, but was more the catalyst than the primary cause for expanding the theater of war. As the two monarchies sought to attack their adversary on every front, they formed opportunistic alliances with smaller states that enmeshed local disputes with their own.

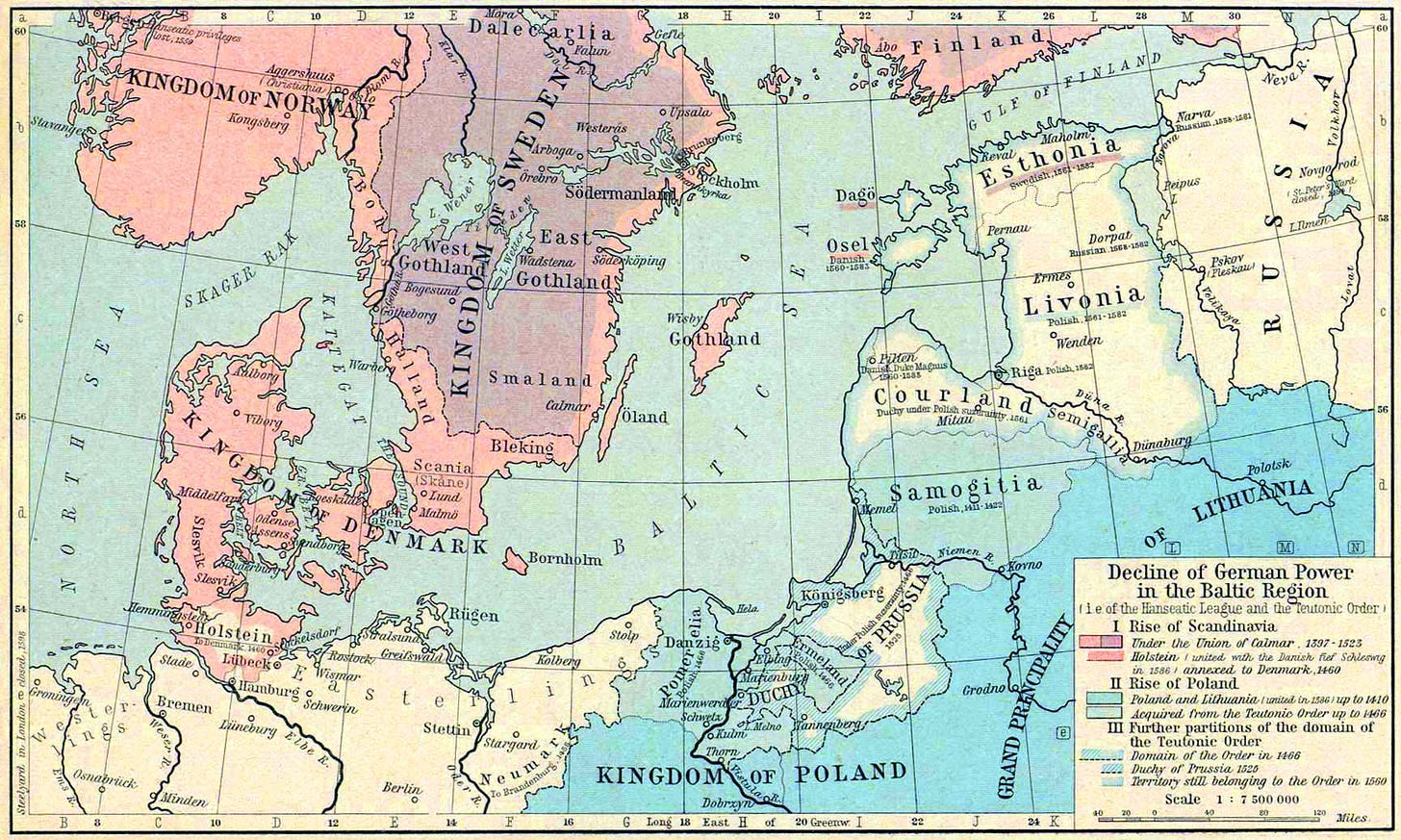

Something similar can be seen in the way Russia got pulled into these conflicts. The Baltic Sea was yet another “natural” theater of war in which Russia, Denmark, Sweden, Poland-Lithuania, and several small German states contended for shares in the rich Baltic trade. Although there was some overlap between these states and participants in the great coalitions of Western Europe (e.g. Denmark, Sweden, and Prussia), these wars were fought for very different stakes and never became Siamese wars.

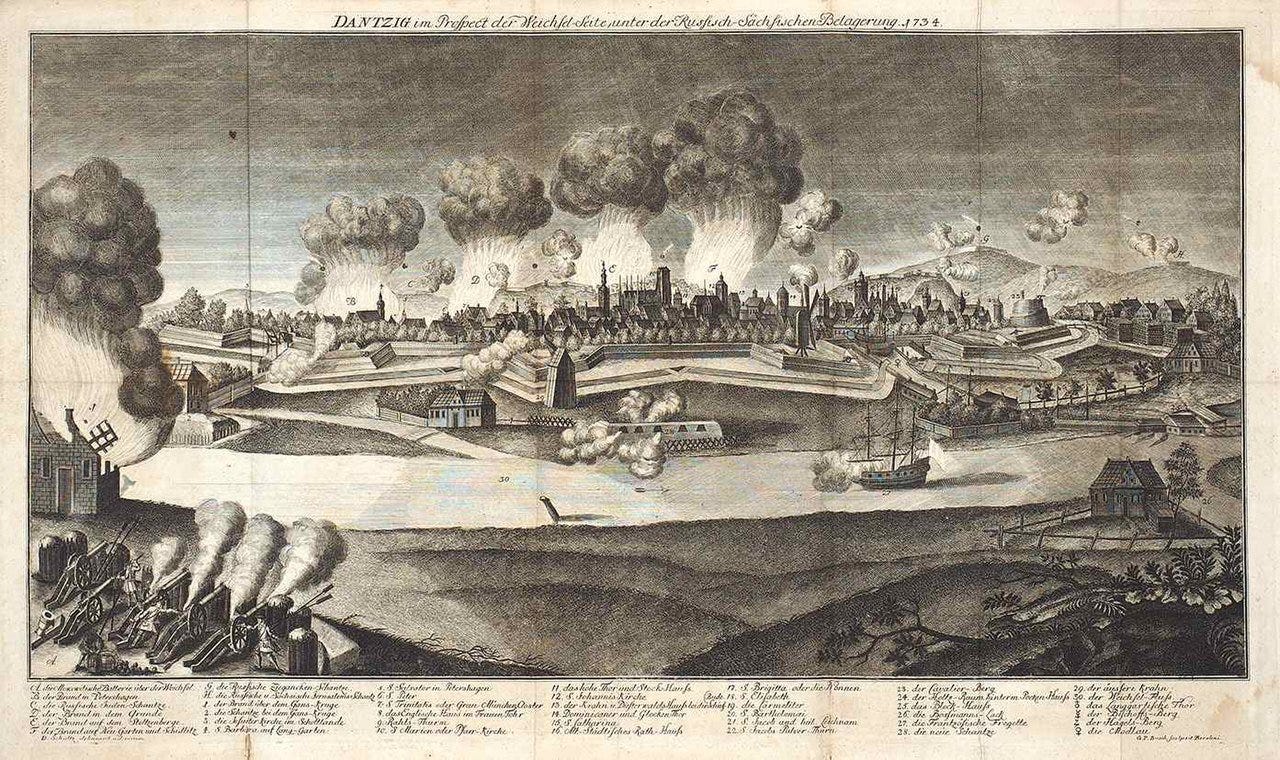

Over time, however, they merged. The War of the Polish Succession, in which Louis XV sent an expedition to Danzig to support his father-in-law’s bid for the Polish crown, was the first time French and Russian troops came into direct conflict with each other. After the fall of Danzig in 1734, the rest of the war was fought mostly between France and Austria in their traditional battlegrounds of Germany and Italy, but the arrival of 10,000 Russian troops on the Rhine in 1735 hastened peace negotiations and marked a new era in European power politics.

Thenceforth, Russia was locked into the Western alliance system. Issues on Poland’s eastern border became inextricable from those at the opposite end of the continent, as all of Europe became one large theater of war. Russia took part in every major coalitionary war of the century: the subsequent War of the Austrian Succession, Seven Years’ War, Napoleonic Wars, and so forth.

Proximity alone was not enough to guarantee this. A third principal theater of war in Europe which overlapped with the other two was in the southeast, where Austria, Poland, Russia, and the Ottomans competed for primacy. Although these wars fleetingly intersected with those to the north or west, it was not until the 19th century, shortly before its demise, that the Ottoman Empire got drawn into the European alliance structure in any meaningful way (religion was just one major reason for this).

New Horizons of Technology

If geography and political configurations shape theaters, so too does a third factor: technology. Rail turned what had traditionally been three separate theaters in northern France in the 18th century into a single theater of operations in 1914 and again in 1940. In 1941, automobiles and trains turned the entire 1,500-km Eastern Front from St. Petersburg to the Black Sea into a single continuous theater.

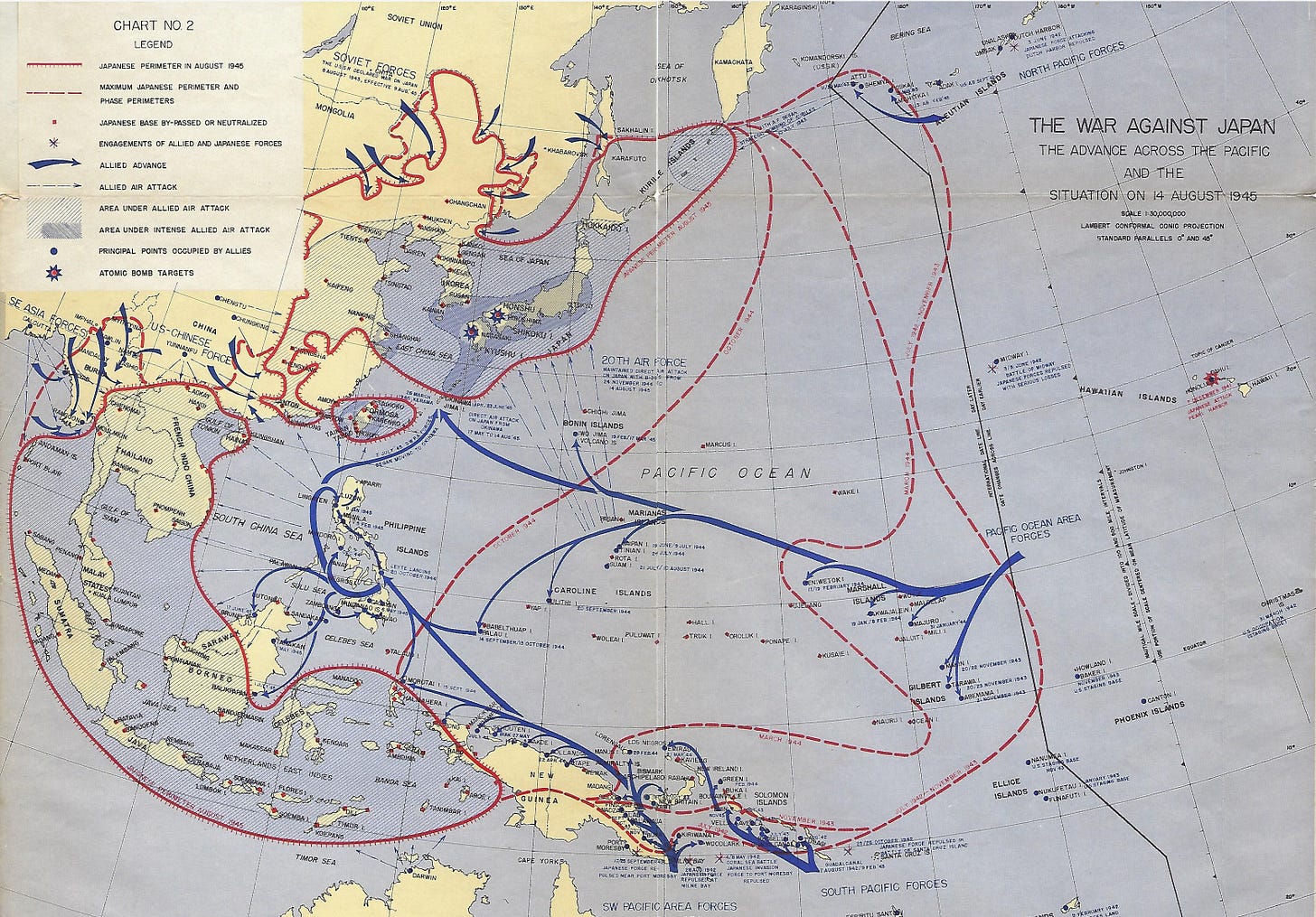

This is even more apparent at sea. Japanese and American expansion into the Pacific in the late 19th century perhaps foreordained an eventual conflict, but technology enabled its scope. As late as the battleship era, theaters of operation were highly localized. The Sino-Japanese and Russo-Japanese Wars were mostly confined to the Yellow Sea, while in the First World War they took place mostly in the North Sea.

In the Second World War, land- and carrier-based aviation and oil-powered fleets drastically extended the area over which individual naval campaigns could be fought. These operational factors drove the Japanese to contest a much larger area than they otherwise might have, ultimately creating a theater of war that stretched over 12,000 km from Hawaii in the east to the Bay of Bengal in the west, 6,000 km from the Solomons in the South Pacific to northern Japan.

These same sorts of calculations are now being made in Washington and Beijing. The island of Taiwan is the immediate point of contention, but that raises considerations about force projection and sustainment across the Pacific. Although it is by no means certain that China and the United States will fight a hot war in the 21st century, ballistic missiles and longer-range aircraft have the potential to turn the entire Western Pacific into a single theater of operations, while extending the theater of war unimaginably far.

Thank you for reading the Bazaar of War. Please like and share if you enjoyed, it helps more people find this. You can also support with a paid subscription, supporters receive the critical edition of the classic The Art of War in Italy: 1494-1529 and get access to exclusive pieces.

You can also support by purchasing Saladin the Strategist, in paperback or Kindle format.

Thanks for an Amazing article BCD. There are always these theaters of wars existing and absolutely there is always an effort made for people to ignore these as Cause and Effects for Those holding these Lands.