The Patterns of Operational Dynamics: A Brief Typology

One of my favorite themes with The Bazaar of War is how certain operational dynamics recur across vastly different times and places: comparing the positional warfare of early 18th-century Flanders to the trench warfare of World War I, for instance, or likening the decisive campaigns fought between Greek city-states to the French at Dien Bien Phu; more recently, looking at how several converging factors led to similar patterns between Arabs on the Byzantine frontier and inter-tribal Native American warfare.

Operational art is deceptively subtle. It is easy to look at the sweeping arrows on a campaign map and admire the elegant maneuvers of a successful offensive, or imagine how the losing side might have done things differently. Effecting those maneuvers is not so easy. Strategic prerogatives, tactical reality, logistical limitations, and the nature of the ground all impinge on a general’s freedom of action, while enormous amount of staff work goes into synchronizing the movements of large bodies of troops over great distances in the face of enemy resistance.

Material constraints shape the broad patterns of a given theater, defining the bounds within which an individual commander can work. There are three principal factors at play:

Mobility afforded by the terrain and infrastructure

Density of forces

Logistical means vs. requirements

It is worth sketching out the various permutations.

Open Ground

Most wars are fought on ground that affords free movement: terrain that allows tactical mobility with sufficiently dense road/rail network for operational mobility. This offers the best chance at decisive victory and the worst risk of catastrophic defeat; all else being equal, militaries concentrate their greatest efforts in these geographies, relegating more difficult terrain to the status of secondary fronts/theaters (indeed, favorable operational conditions alone can make a particular theater a strategic priority). Within such theaters, however, much depends on the quantity of troops and the efficiency of their supply.

1. The Billiards Table

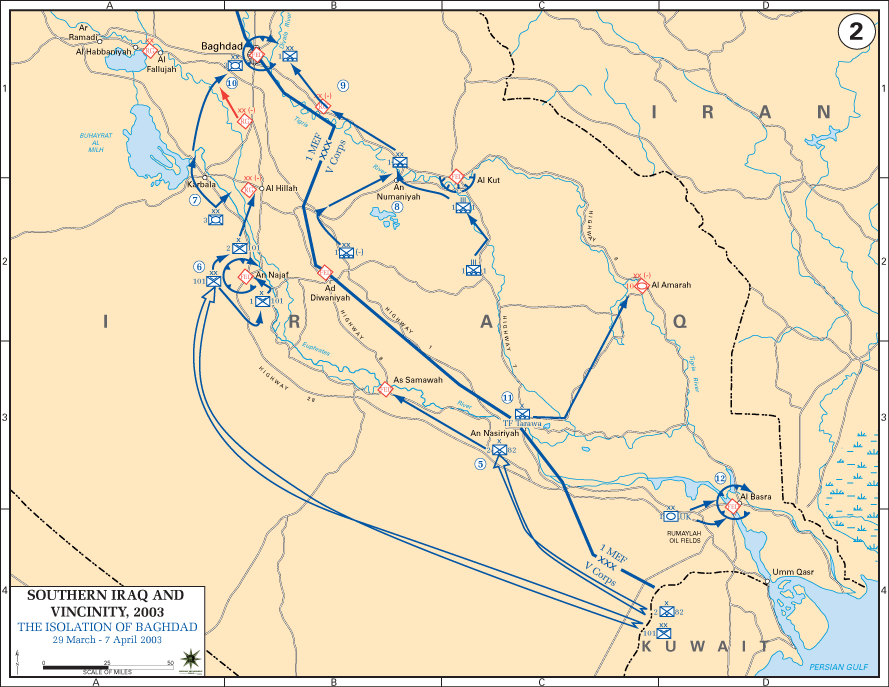

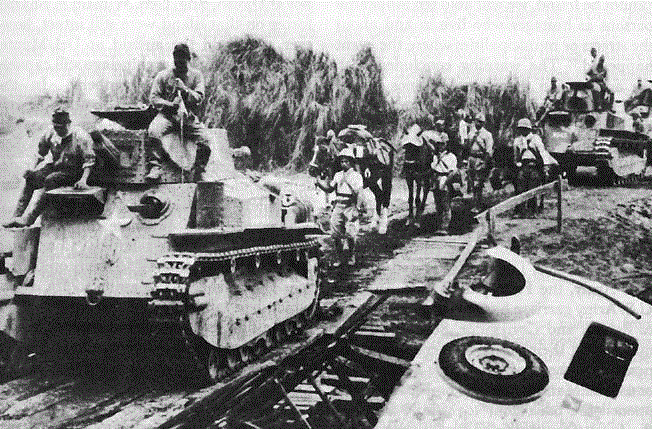

In the “classical” style of warfare that prevailed from antiquity through the 18th century, armies were small relative to the area in which they operated. Whether marching as a singular body or as several dispersed corps, they had plenty of room to maneuver freely around the enemy. There are some examples of this in modern warfare too, such as the armies which invaded Iraq in 2003 or fought in the North African desert campaigns of the 1940s.

The better the logistical apparatus of such an army, the tighter and swifter its movements can be. Logistics both furnishes the means and defines the objectives of maneuver: it enables the forward flow of supplies, and also presents the enemy with a target for exploitation. This gives “classical” warfare its characteristic pattern of rapid movements followed by a positional fight in the form of a siege or battle. The reason that Hannibal gave battle at Cannae, for instance, after evading superior Roman armies for over a year, was that he had just captured a major supply depot there and was forced to defend it.

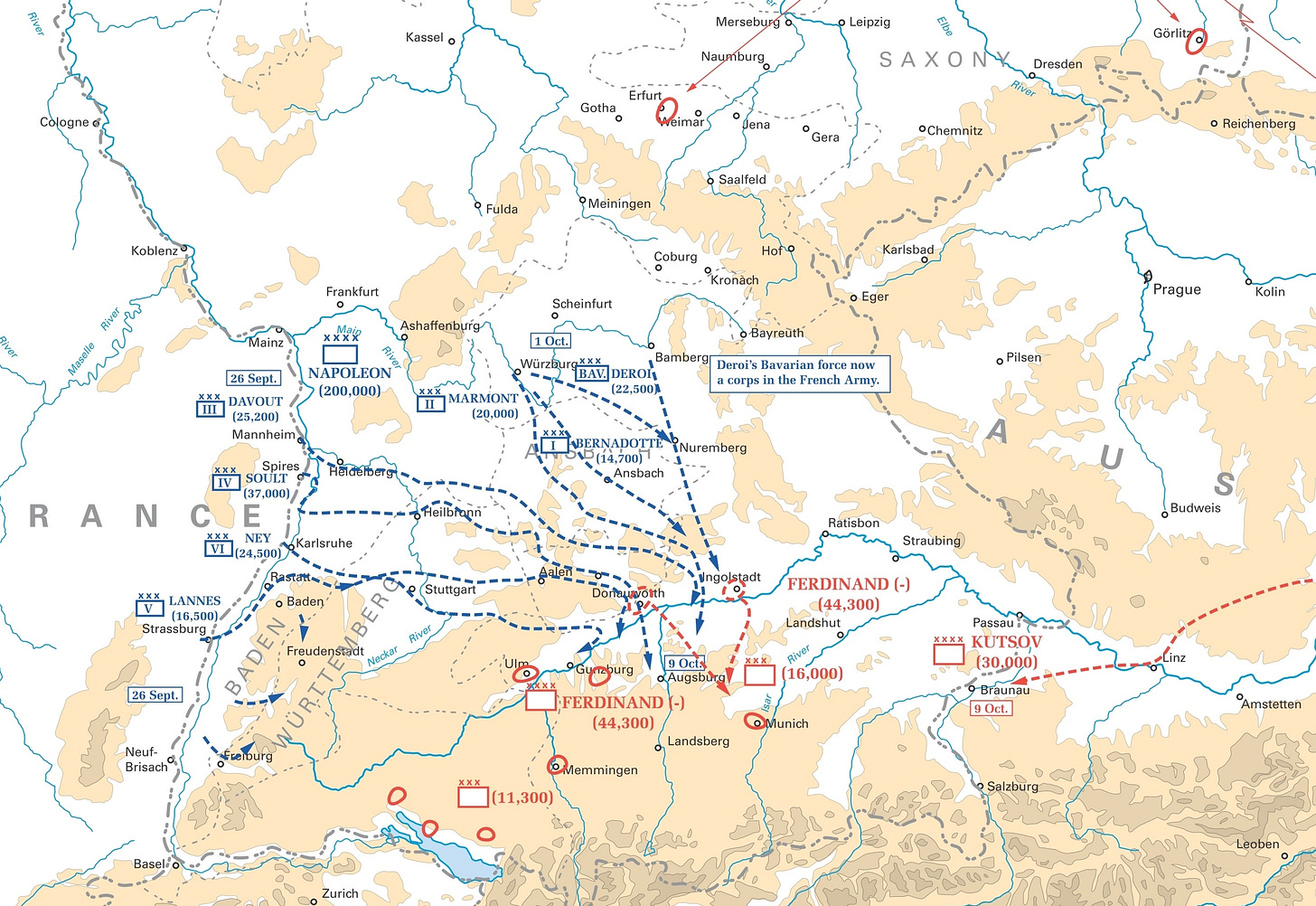

When armies are more tightly tied to their lines of communication by a series of depots and magazines, the capture of one can unseat their entire position. Alternatively, simply occupying a position across these lines, as Napoleon did with his Ulm maneuver, can be sufficient to compel an army to surrender.

An army that lacks such efficient organization—premodern armies that lived entirely off the land, or modern armies that lack trucks—resemble more indistinct blobs. They are forced to sprawl out over a wide area to forage or draw supplies, and their movements are slow and shambling. This greatly reduces operational effectiveness, foreclosing complex maneuvers, as seen during certain phases of the Thirty Years’ War: fighting devolved into campaigns of devastation and counter-devastation, as armies struggled to raise contributions from provinces that had already been bled dry.

Such deficiencies can be exploited by more efficient armies. The Crusaders of the later 12th century developed a system of responding to invasions with tightly-disciplined marches from one castle or fortified camp to another. This forced the enemy army to remain concentrated as they approached, preventing it from dispersing to forage; and since the invaders lived entirely off the land, they soon had to retreat for lack of forage unless they could quickly bring about a decisive battle.

Something similar happened during the fall of the Philippines in 1941. MacArthur had dispersed his supplies around Luzon in anticipation of fighting the Japanese on the beaches, but lacked the transport to shuttle them back after his plan failed. Once his army reconcentrated on the highly defensible Bataan Peninsula, it quickly ran out of supplies and was forced to surrender.

2. The Crowded Front

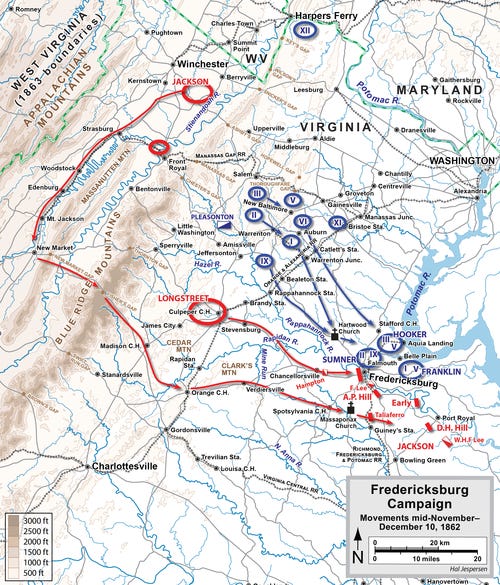

As the density of troops in theater increases, there starts to emerge a front: a rough line that divides the theater in two, defining fixed rear areas. A front need not be continuous, and large detachments may even be able to penetrate it; but for various reasons, both tactical and logistical, they cannot remain there long—such a virtual front was formed by the Rappahannock River in the Eastern Theater of the US Civil War.

The solidity of a front increases with force density—this refers less to troop numbers than to combat power (an admittedly vague measure). Longer-ranged and more lethal weapons allow fewer troops to hold the line, as we see in Ukraine, where the 1000+ km front is held by just a few hundred thousand on each side. Higher density at any rate presupposes high logistical capacity, but an army’s ability to exceed static requirements greatly shapes the tempo of operations.

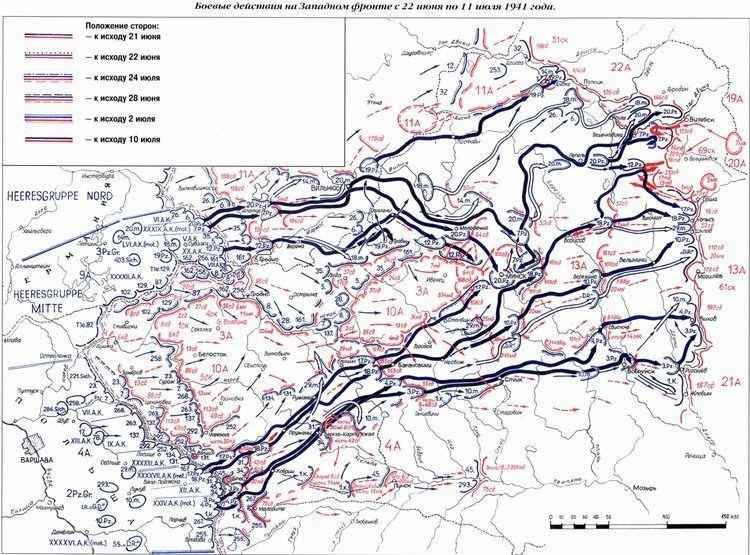

So long as the supply train can keep up with advancing troops, the dynamics are not too dissimilar to “classical” operations. Instead of discrete bodies of troops, large concentrations break through the enemy line, work around the flanks of his major positions, attack his logistics, and cut off his retreat. It is only during the initial phase that things differ markedly from the classical model: operational planning consists less of movement than of synchronizing tactical engagements to effect a break-in.

When logistics can meet, but not exceed, these high demands, movement of the front grinds to a halt. The classic example is the Western Front in World War I: rail lines fed the artillery’s prodigious appetite for ammunition, but armies lacked the capacity to push beyond the railheads to exploit breaches in the enemy’s lines. As already mentioned, very similar dynamics took place in the heavily-fortified northern theater of the War of the Spanish Succession, where rivers and canals played the role of railroads: they could ferry enormous quantities of gunpowder and provisions to the front, but advancing past the enemy’s defensive line usually required taking several adjacent fortresses to secure these avenues. A combination of tactical and logistical limitations likewise shapes Ukraine today: although the nature of the fighting itself is very different from WWI-style trench warfare, similar operational-level dynamics emerge for identical reasons.

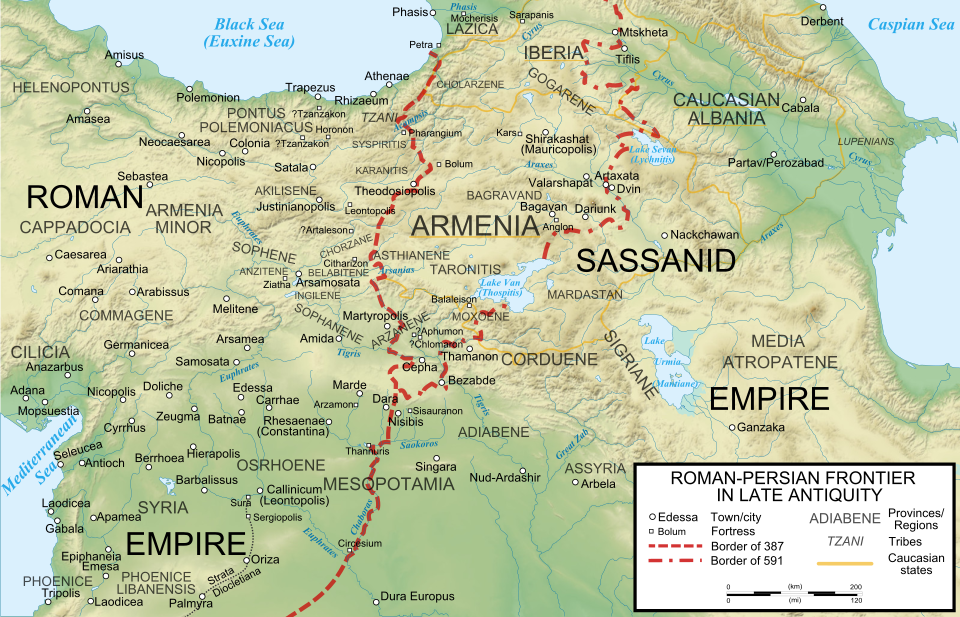

The Roman-Persian frontier in Late Antiquity fell somewhere in the middle. The northern plains of Mesopotamia were fertile enough to sustain large concentrations, making it a risky proposition to advance too far into enemy territory without reducing the intervening fortresses, even if smaller armies could still live off the land. Campaigns in this theater therefore consisted mostly of sieges of frontier forts, but allowed some large-scale incursions deeper into enemy territory.

3. The Desolate Frontier

At the opposite end of the spectrum, certain geographies make logistical sustainment difficult no matter what, limiting troop densities by default. Although smaller armies may still be able to conduct complex maneuvers like their better-supplied counterparts, it is harder for them to accomplish anything decisive. The difficulty of keeping fixed positions in supply makes them relatively less important, which in turn makes it difficult to force the opposing army into a major engagement.

Only rarely, as in the Arab-Byzantine frontier from the 7th to the 10th centuries, does such a theater become the principal one in a war. At the peak of the Abbasids’ incursions, very large armies indeed crossed the frontier, but the inhospitable country required them to march in dispersed columns and to keep on the move.

Such dynamics are mostly a phenomenon of pre-motorized warfare. Once logistics no longer relied on forage-hungry draft animals, the nature of the country mattered only insofar as it affected mobility. The closest analogue in the modern world is situations where both sides are subject to the tyranny of distance, where transport is a major constraint. This somewhat describes Axis forces operating at the end of their logistical tether in North Africa, where supplies were bottlenecked by the port capacity of Tripoli, and again by the limited number of trucks in the vast distances. Perhaps a better example is the remoter parts of the Eastern Front in that same war: in 1942, Army Group A pursued the Soviet North Caucasian Front into the empty Caucasian Steppe, supported by a wholly inadequate road and rail network.

Constricted Terrain

Geography is not always so cooperative: mountains, forests, and swamps severely restrict cross-country mobility. These types of terrain leave more room for operational maneuver than one might suspect, as even on open ground most operational movement is confined to major roads and rail lines—provided there is a sufficient number of passes/paths, an attacker can usually advance through even the most difficult terrain. But the ground nevertheless does significantly alter the dynamics.

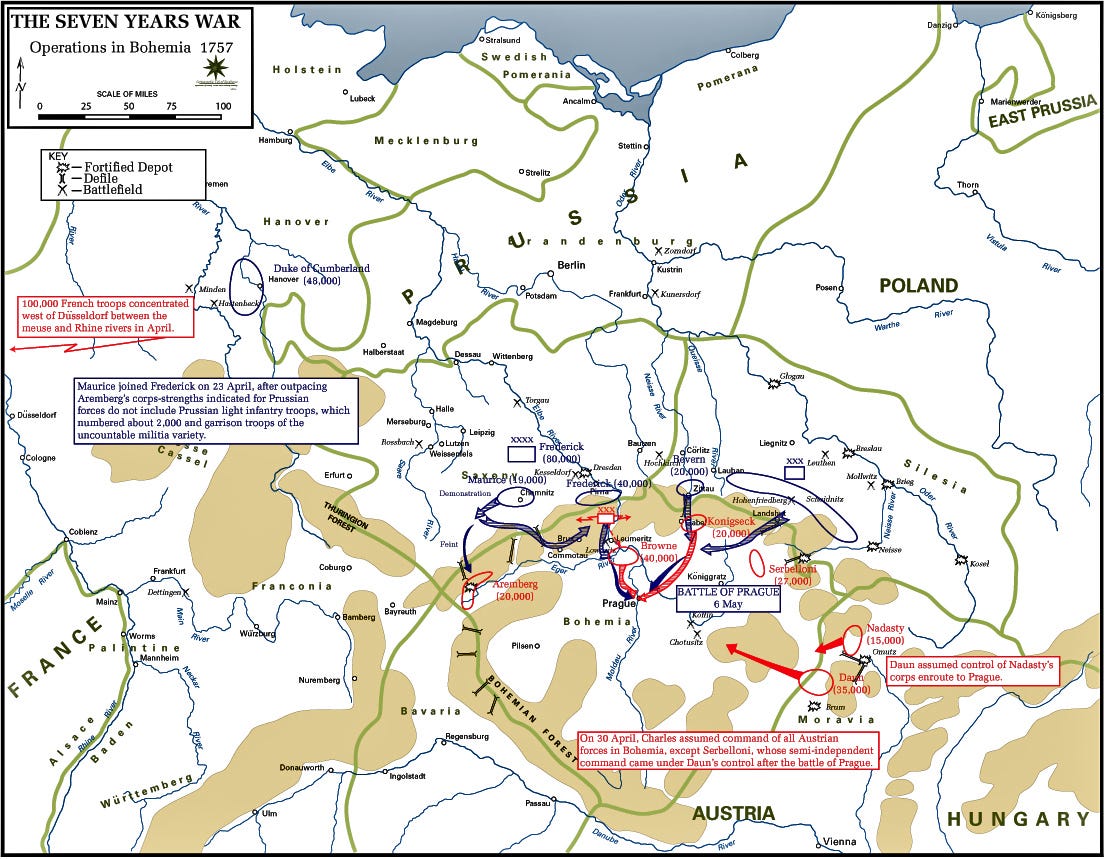

Constricted terrain poses an apparent paradox: it is easy to defend tactically, but difficult to defend operationally. Passing columns are extremely vulnerable to ambushes from concealed positions, but the lack of lateral communications makes it very difficult for the defender to reinforce a sector where the enemy is attacking in strength.

This is especially true when an obstacle is long but narrow, acting more like a river than a theater unto itself. So long as an attacker can conceal which axis he has reinforced, he stands a good chance of breaking through and dislodging the entire defensive line. Frederick the Great was constantly able to break into the Bohemia with several columns marching on converging axes—even if the Habsburgs could successfully defend the principal axis, another Prussian corps would inevitably get through and endanger their rear.

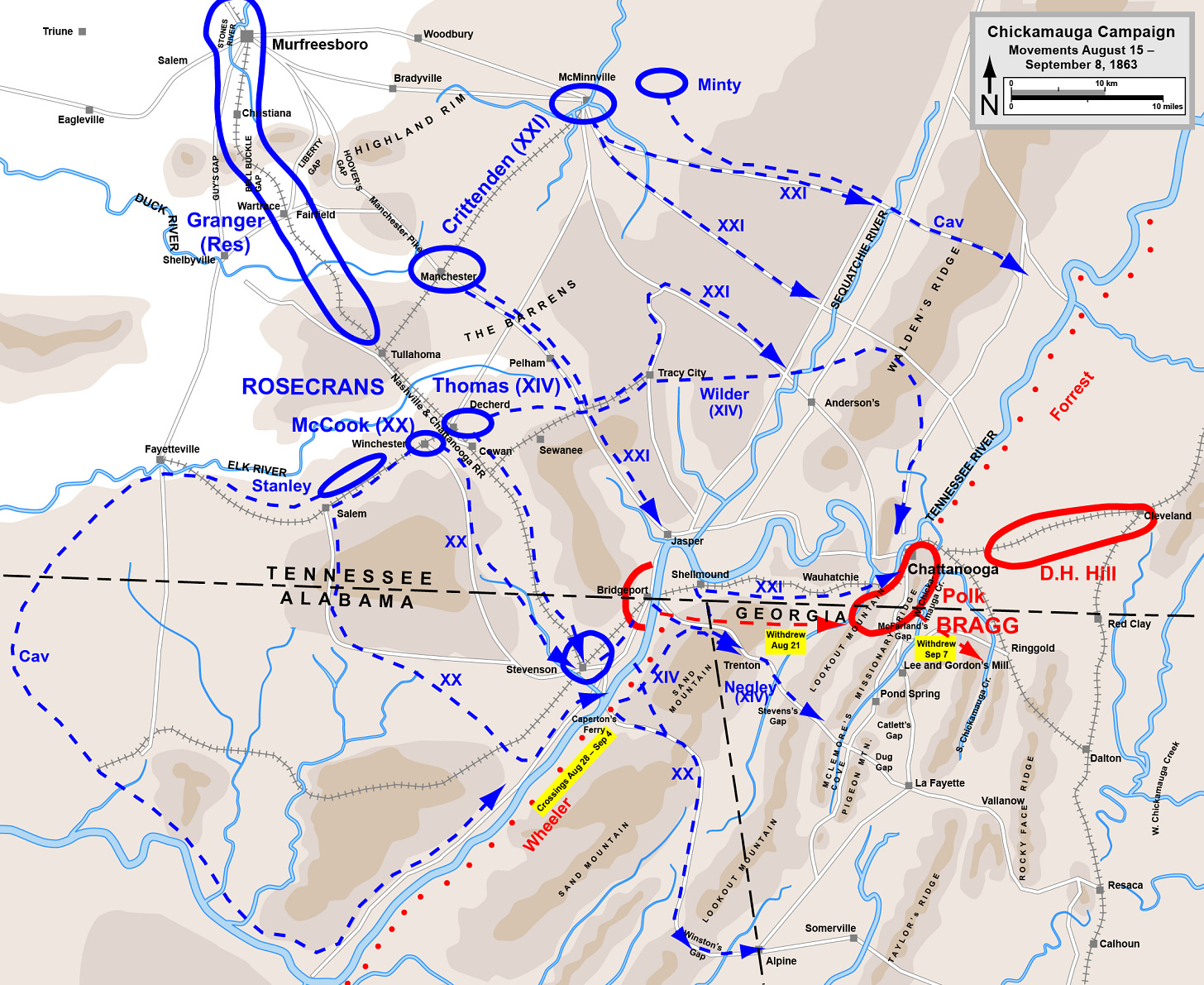

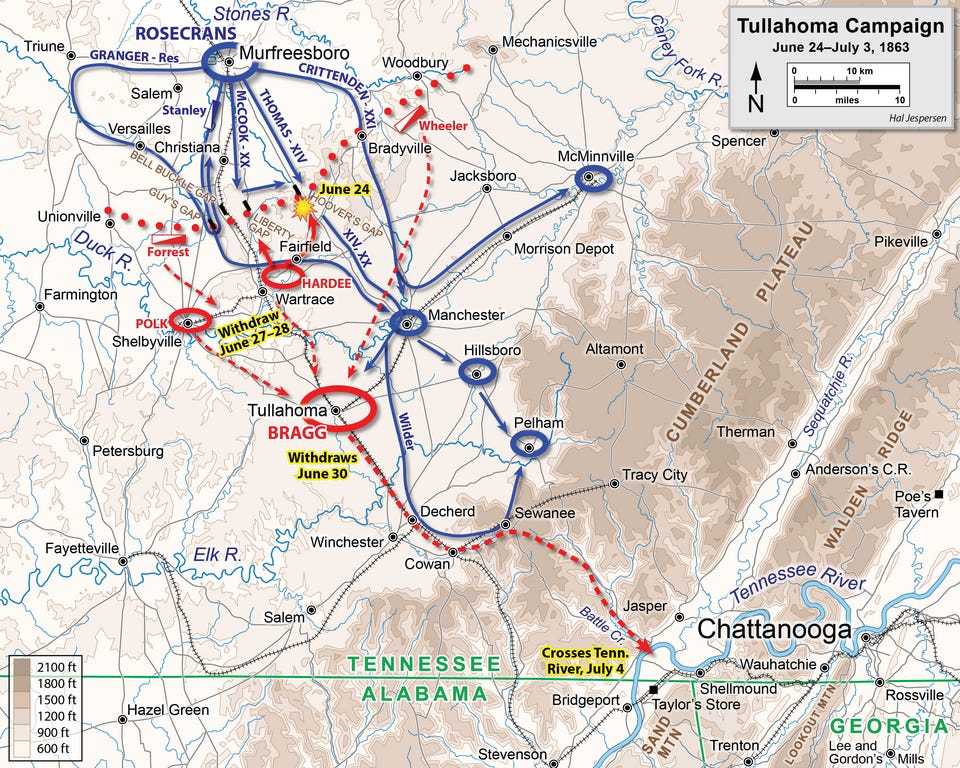

It is also what Rosecrans did in southeastern Tennessee during the Tullahoma Campaign of 1863. His opponent, Confederate general Braxton Bragg, held a 50-km frontage along central Tennessee’s Highland Rim. This was barren country that could not support large concentrations, and Bragg’s 50,000 men were furthermore spread thin guarding four major gaps. Rosecrans feinted toward the western end of Bragg’s line, then broke through in strength further east. This imperiled the rail line to the Confederate base of operations at Tullahoma, and Bragg was only able to squeeze out of the trap because heavy rains slowed the Union advance. Despite his escape, Lincoln called the campaign “the most splendid piece of strategy [i.e. operational art] I know of.”

When mountains or jungles constitute a deep obstacle, it is correspondingly more difficult for the attacker to win a decisive victory. There is no open ground to the immediate rear to exploit, making it correspondingly harder for parallel columns to complete an envelopment. The attacker can only concentrate his forces on nodes where several routes converge—predictable points which the defender can fortify or withdraw from in good time.

This explains Rosecrans’ failure to destroy Bragg in the subsequent Chickamauga Campaign, in which he pursued the Confederates through the much wider Cumberland Plateau to Chattanooga. Crossing 75 km of mountainous terrain in several columns, he was unable to bag any significant concentration of Confederate troops, and was left scrambling to re-concentrate his own army in the face of a Confederate counterattack. The ensuing Battle of Chickamauga was a bloody Union defeat; although only a tactical defeat, not operational—Rosecrans was left holding onto Chattanooga—it precipitated his relief a month later.

Armies can mitigate these disadvantages with specialized units that have better tactical mobility. Japanese jungle fighters were able to outflank one British position after another throughout the Malayan Campaign, and in the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh War, Azerbaijani special forces crossed the mountains to attack Shusha from the rear, disrupting the Armenians’ defenses there. Success in such cases is still highly contingent: in both examples, the attacker faced an unprepared and demoralized enemy, while the Japanese were further aided by the ability to conduct occasional amphibious landings.

Dense and Constricted

These sorts of maneuvers are only practicable with a relative low force density. Above a certain number of troops, however, operational movements resemble more the cumbersome advances of high-density, low-logistical-capacity fronts on flatter terrain. Individual mobility corridors can be defended in strength, exploiting their inherent tactical defensibility to make breakthroughs necessarily slow, leaving the defender enough time to reinforce critical sectors even by circuitous lateral routes.

This was the case in the Italian theater of World War II. The front spanned the entire width of the peninsula, forcing the Allies to fight the length of the Apennines. The Germans occupied the high ground overlooking all mobility corridors to the north, forcing their enemies to painstakingly evict them from one position after another. Despite every advantage in manpower, equipment, and logistics, it took the Allies nearly two full years to break into the northern plains. Korea likewise saw the front shift up and down the mountainous spine of the peninsula from 1951 to 1953.

Likewise, in the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh War, it took the Azerbaijanis five weeks of intense fighting to advance the 45-km straight-line distance from Jabrayil to Shusha—and only with the aid of reinforcements from the stalled northern front.

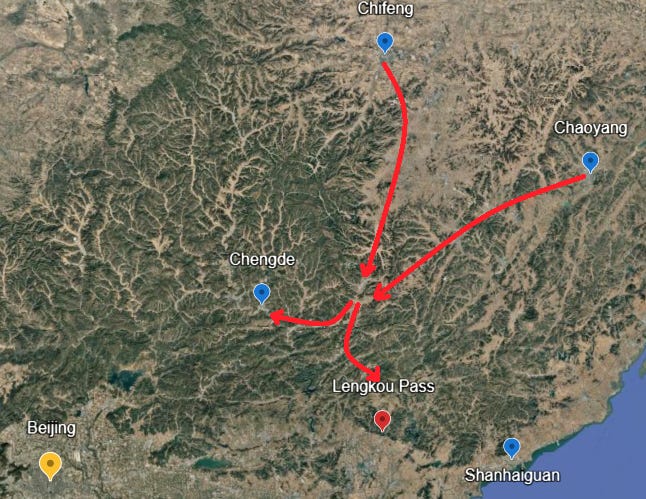

These dynamics are also shaped by the depth of the obstacle. In the shallower but wider mountains of northern China, Zhili and Fengtian forces stalled out for several weeks in 1924 until the latter managed to break out into the plains below.

When large-scale logistics are not practicable, things usually default to a defensive victory, as attackers rarely wish to risk getting bogged down in major fighting in difficult terrain. This explains the dearth of large-scale fighting in the Alps throughout history—when an attacker unable to overwhelm the relatively small garrisons of mountain fortresses, he usually withdrew.

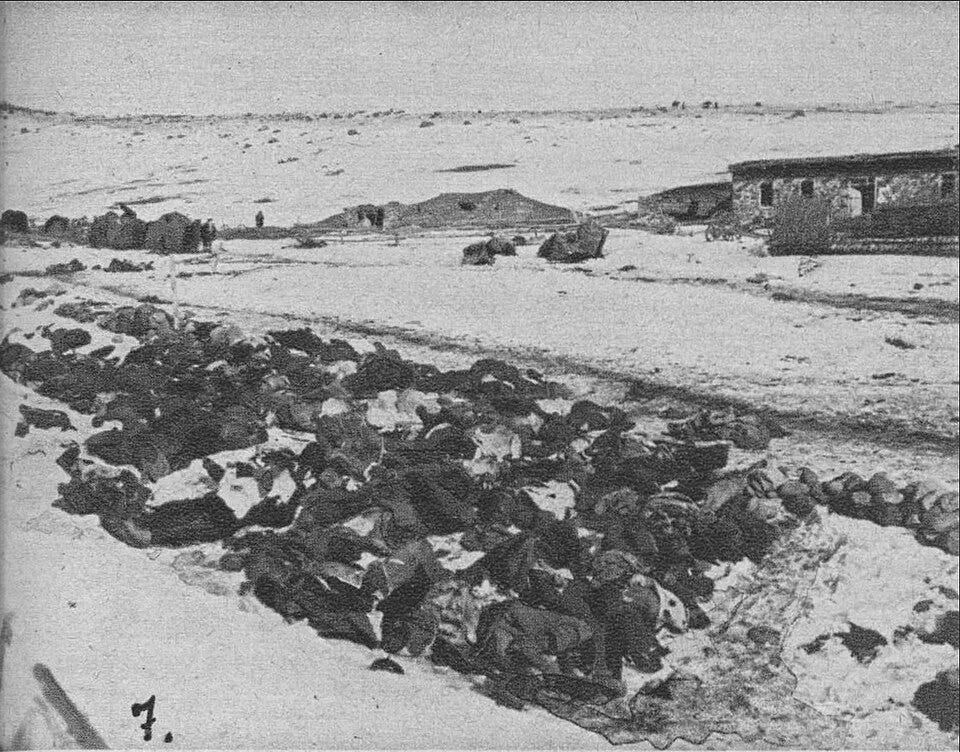

To do otherwise is to risk the fate of the Ottomans on the Caucasus Front of World War I. Although their Third Army was able to maneuver around Russian positions and appeared on the verge of a crushing envelopment, it could not sustain itself once winter set in, and ended up suffering over 90% casualties—many of which suffered frostbite or froze to death.

Conclusion

The above is only a sketch of the major conditions that shape operational dynamics—there are many other factors at play. Strategic prerogatives exert their own influence, and the list of material factors is far from exhaustive. This nevertheless serves as a useful template for evaluating campaigns and making sense of generals’ decisions. It will be a point of departure for future Dispatches which look more deeply at certain dynamics and individual case studies—including one in the not-too-distant future on the Tullahoma-Chickamauga campaigns mentioned above.

Thank you for reading The Bazaar of War, please like and share to help others find it. A lot of time and research goes into creating these pieces — you can help support with a paid subscription. This gives you access to monthly long-form exclusives which examine the deeper dynamics behind selected historical episodes (preview them here). You also receive the critical edition of the classic The Art of War in Italy: 1494-1529.

You can also support by purchasing Saladin the Strategist, in paperback or Kindle format.

Thank you, a brilliant piece!